Book Review: "The Two-Parent Privilege"

An economist looks at the surge of single parent families.

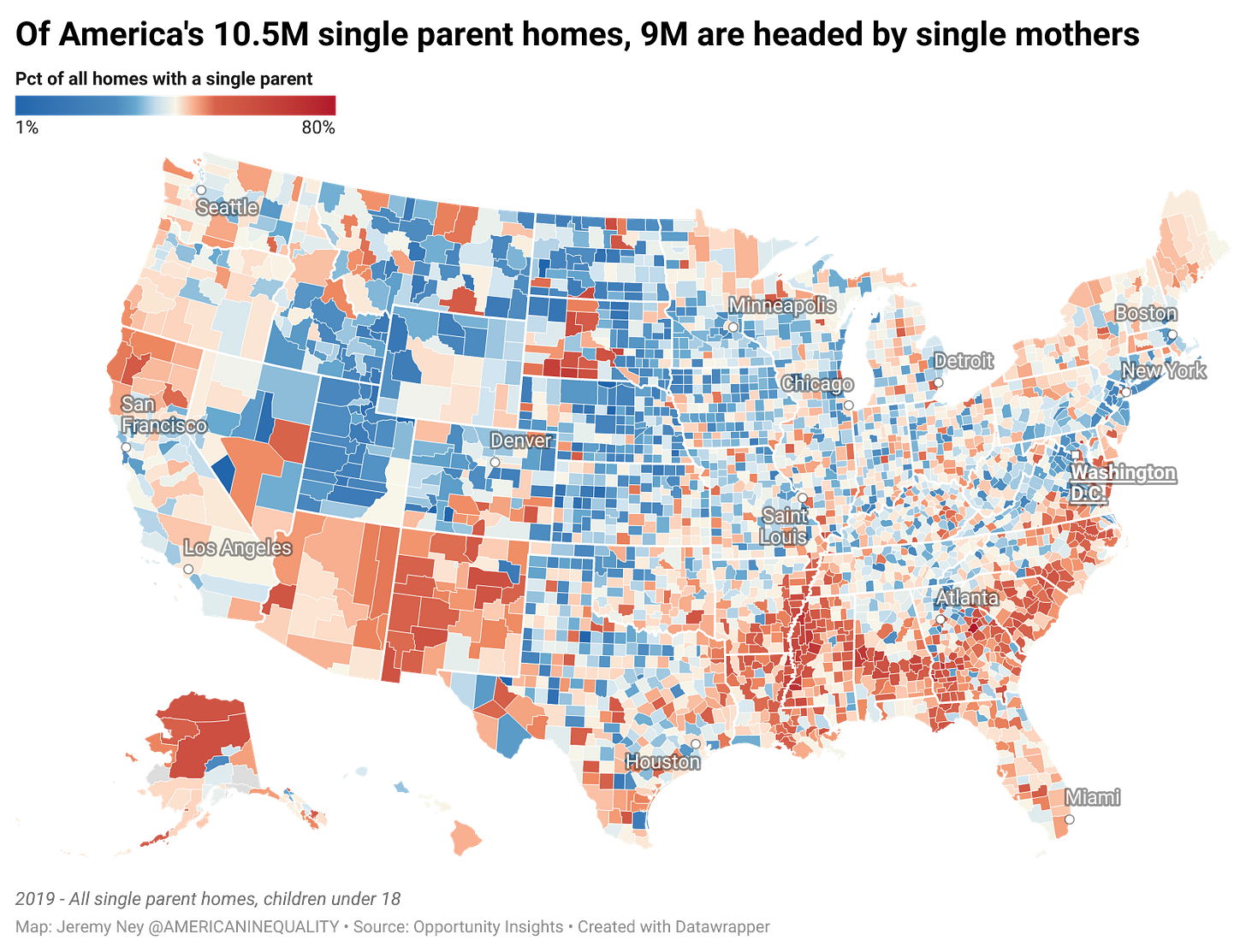

I like thinking about culture war topics from the perspective of forecasting and so Melissa Kearney’s new book, The Two-Parent Privilege, seemed like it would be a good background for a new project. There are a lot of people talking about how America has bifurcated into two societies. People in the upper middle class have college degrees and own their own homes, and working class Americans do not. But Kearney argues that one of the biggest distinctions is that the children of the upper middle class have fathers and the working class does not. This is a relatively recent occurrence. In 1960 only about 5% of children were raised in single parent homes, but then:

over the past 40-plus years, American society has engaged in a vast experiment of reshaping the most fundamental of social institutions—the family—and the resulting generations of data tell us in no uncertain terms how that has played out for children.

What is that sparked this “vast experiment” of single parenting? Kearney is an economist and she argues that the core problem is that “the economic attractiveness of non-college-educated men has been diminished.” She claims that men without college degrees don’t make enough money for women to see them as marriage material, or men to see themselves as marriage material. This wouldn’t cause a decline in marriage, if college graduation was gender balanced, except that there’s been a massive gender disparity in college attainment for the past few generations, which I’ve covered extensively before (see Forecasting the College Enrollment Gender Gap).

The children of single parents often go on to become single parents themselves, whereas the children raised with two parents go on to find a spouse of their own. Kearney argues that “if left unchecked, these class divisions will deepen and perpetuate across generations.” Her argument is that the problems facing boys and young men have happened on such a scale that it has divided our country—not by gender, but by social class—and threatens to permanently calcify us into two societies: “The more boys struggle and fall behind, the less prepared they will be as adults to be reliable economic providers as husbands and dads. This creates a vicious cycle.”

The Two-Parent Privilege is not an exciting book. The conversation around parenting and families and marriage and gender strikes deep in culture war territory, so she deliberately avoids the human narratives that make books emotional and instead sticks with data. The result is that Kearney writes the way I imagine an exhausted surgeon at the end of a long shift would describe the injuries of a dying patient. It’s a very clinical and detached assessment of the situation. In response, people have written some of the most deranged hot takes I’ve seen in years. But it’s not just people in the mainstream culture who are responding angrily to this problem. Kearney describes hostile responses at academic conferences when she raises this issue, being silenced when asking questions, being accosted by famous economist because she spoke about these problems, and in an interview this was described as “forbidden research” in academia.

But Kearney’s intent was to talk about the topic in a data-driven way, so I think it deserves a data-driven review. I want to answer a few questions. Is the impact of single parenting on our society as bad as Kearney claims? Is economics really what caused this situation? And why did this surge of single parenting start so suddenly?

Correlation or Causation?

The children of single parent homes have much worse outcomes on average, but are these problems due to single parents correlating with lower income households, or is it actually caused by having only one parent? Kearney argues some of both. Even adjusted for income, kids raised by single parents are less likely to graduate high school, less likely to graduate college, more likely to go to prison, more likely to be unemployed. Why? Being a parent isn't just expensive, it’s also time consuming and exhausting. Single parents are more stressed out and more stressed out parents show less “emotional warmth” to their kids. They don’t have as much time to take them to after school activities, even when they’re free. The kids are also more likely to get in trouble because they just have less supervision. She also shows numerous studies that find that boys do much better with a male role model in the home.

The bulk of the book defends the argument that these outcomes are because of how challenging it is to be a single parent—that it’s causal, not correlation. I’m skipping over most of this because even Kearney’s critics acknowledge that she’s probably right on this. For me, the interesting part is about what’s driving this surge in single parent households.

What caused the surge in single parent households?

Kearney rules out a number of possibilities here. It doesn’t seem due to increasing levels of abuse. Mostly it’s due to the parents not being married. You might say well, even if they aren’t married maybe they're cohabitating, but in the United States, that’s just not actually happening in practice. Kearney uses marriage rates as a proxy for single parenting. She doesn’t talk about marriage because she’s a conservative (she’s a feminist, pro gay marriage, and supports more social safety nets), but rather, she talk about marriage because in the United States, parents who aren’t married overwhelmingly end up drifting apart. So then why aren’t parents getting married? Is it due to divorce? Mostly, no. It’s mostly due to them never getting married in the first place. So the question boils down to why aren’t parents getting married in the first place?

Economics is often criticized for treating humans as hyper-rational agents, rather than emotional human beings, and when it comes to mathematically modeling marriage, economists have very much lived up to that reputation:

from the perspective of a woman considering whether to marry a man, the ‘gains to marriage’ will depend not just on how much he would bring, but on how much she could make on her own, if she chose to work. This is a standard economics approach to modeling marriage.

Economists model marriage economically. They assume that women are hyper-rational agents, who get married based on the financial return a husband will provide. To put it bluntly, the two core assumptions of the economics model of marriage are 1) that women are sociopathic gold diggers and 2) that nearly every man is a desperate loser who’ll marry any woman who smiles at him. Embarrassingly for everyone, this model was very accurate at predicting marriage rates. Or at least it used to be. But more on that later.

The standard model of marriage in the economics literature posits that as female wages rise relative to male wages, there will be a reduction in marriage because the returns to marriage are lower. This means that women have less to gain by entering into a marriage contract.

But is it really true that in America—the wealthiest nation in human history—roughly a quarter of the men are just too damn poor to marry? Kearney argues yes. She says this is exactly what happened in the United States starting in the mid-1980s, when manufacturing jobs in the United States were outsourced. College educated men remained “economically attractive” partners and “marriage became relatively more common among elites.”

Kearney says,

Reversing the widespread decline in marriage and the corresponding rise in nonmarital childbearing and single-mother homes will likely require reversing the effects of the seismic economic forces that have disadvantaged non-college-educated men. Addressing these challenges on a large scale will require a tremendous amount of political will and years of time. Or they will just continue to calcify and get worse.

On the one hand, I’m sympathetic to this because I agree with her that I’d like to see things get better for working class men, and even though it isn’t mentioned here, working class women too. But on the other hand, I’m not completely convinced that the root cause of single parenting is economic. I have a number of problems with her narrative.

First, Kearney argues that this situation began in the 1980s. She says that “The changes in marriage patterns that I describe have all taken place after the cultural revolution of the 1960s and 1970s” [emphasis Kearney’s]. What rhetorical strategy does Kearney take to convince her audience that this began in the 1980s? Mostly by starting the data visualizations in the year 1980 and not showing the audience anything that happened prior to that1. I don’t think this was a deliberate strategy, it was likely that Kearney just zoomed in on the period she was interested in. But it makes it difficult for the casual reader to come to any conclusion other than what they’re presented. So what happens if we do look at data prior to 1980?

Well, Kearney is definitely right that there was a bifurcation in the mid-1980s. Absolutely no question about that. Prior to the 1980s, men without a college degree were slightly more likely to get married, but it was so similar, there’s almost no difference. Since the 1980s, a college degree seems to give men a romantic advantage and before that it didn’t seem to matter at all. But this narrative omits the larger picture: the decline in marriage actually began in the late 1960s for non-college-educated men and continued at nearly exactly the same rate for several decades.

Doesn’t it seem a little coincidental that the “cultural revolution of the 1960s and 1970s” caused marriage for men without college degrees to decline at almost exactly the same rate as the economics of the 1980s? Doesn’t it seem a little coincidental that this cultural revolution’s impact on marriage ended at the exact moment that this economic situation began? And with seamless continuation between the two periods?

Science is about exposing your ideas to falsification. What would falsify this argument that this was caused by economics? Hypothetically, what if you could run a massive experiment where you suddenly inflated the income of non-college-educated men in some towns but not in other towns, and then compare their marriage rates to test this hypothesis?

The Fracking Boom

Kearney looked at areas where the fracking boom during the 2000s led to a surge in wages for working class men and compared it to towns where the wages did not increase. But marriages did not surge, as the economic model of marriage would predict.

Over the past couple decades the replication crisis across the social sciences in particular, and science in general, has called into question major parts of scientific knowledge, from psychology to cancer studies. If this model is really the standard economics approach to marriage, and it doesn’t replicate, then this is a pretty major event in the replication crisis. Kearney hand waves it away by saying that “we are likely in a new social paradigm.” In other fields you would say that the model failed to replicate and this would be framed as another example of the replication crisis, but apparently in economics you’re allowed to just say, it’s not the mathematical model of the world that’s broken, the problem is the world is broken.

If the economic model of marriage had successfully predicted marriage rates, then Kearney would’ve said that was evidence that economics was the cause of the marriage decline. Instead, the opposite occurred, but she arrived at the same conclusion. As I said before, science is about exposing your ideas to falsification. What evidence would falsify Kearney’s belief that the decline in marriage was caused by economics?

The failure of the economic model of marriage leads to a lot of questions. Was the economic model of marriage was never very good to start with? Are women no longer interested in rich men? Do men just not want to get married anymore?

Are Men Retreating from Marriage?

One limitation of this economic model of marriage is that it presents the decision as if marriage is purely based on the decisions of women. But of course, marriage takes two people to decide. Kearney does look at it from the other side and wonders if it’s not just women who are withdrawing from marriage, but men as well. She claims, “Existing evidence shows that when men’s primary economic position has weakened, marriage rates have fallen—that men have retreated from marriage structures.” This seems like a completely reasonable hypothesis. After all, when men lose their jobs, they disproportionately commit suicide because they feel they can’t support their families. So, if they’re withdrawing from life itself, it’s completely reasonable to speculate that they might be withdrawing in less severe ways. But Kearney says she has evidence, not just speculation. What evidence is she referring to?

This is where things get a bit odd. Kearney cites the economics paper, “Gender Identify and Relative Income Within Households,” where the authors take data from the National Survey of Family and Households (NSFH) and look at the income difference between the husband and wife and then ask 1) if the husband and wife report being happy in their marriage, 2) if they think their marriage is in trouble, and 3) if they’ve discussed separation. In all three cases, the wives report being less happy, think their marriage is in more trouble, and report wanting to discuss separation more than their husbands. The authors then say that we could compare the responses from the husbands and wives, but that we’re better off just ignoring the data:

We suspect that such a comparison is not particularly useful. If say the husband is initially the one who is unhappy, he may start to behave in the ways that make the wife unhappy, perhaps even more so.

But why do they think that it’s not useful to compare the responses? They justify ignoring their dataset by saying that, “Such a possibility echoes Al Roth’s Iron Law of Marriage: you cannot be happier than your spouse.”

The important word here is “possibility.” Not evidence. Their data does not echo the Iron Law of Marriage. Their data contradicts this law by showing that husbands are happier than their wives when the husbands make less money. Al Roth won the Nobel Prize for economics. Imagine if a scientist won the Nobel Prize for physics, and then a young physicist found experimental data that contradicted that Nobel Prize winner’s work. It would be the defining moment of that young scientist’s career.

What other supporting evidence does Kearney provide to show that men are retreating from marriage? Quotes from television shows and a conversation she had with an Uber driver.

But maybe Kearney is right

Clearly, women like their partners to be employed. I’ve been on dates where I was asked within the first ten minutes about my finances. Do you own a car? Do you own a house? What do you do for work? What do people who do that for work typically make in salary? Oh, there’s a wide range? What about people who have your job title specifically at the company that you work for? I would’ve saved time if I’d just brought my tax forms along to the date. Plus that economic model of marriage worked for quite a while. And although it seems a bit hand wavey to blame the failure of the model on the social paradigm, maybe she’s right. Her argument is that the economics caused people to stop marrying, then when the economics got better for working class men, marriage was just out of style.

In the early 1960s, only about 5% of kids were in single parent homes. I haven’t looked back much before 1950, but I can’t find any evidence that it was much different at any prior period. We seem to have stabilized at about this level for the past decade or so. If Kearney is correct, and we calcify at this level for a long time, say for a century or more, this is what it would look like:

If we persist at this level for a century or two it’ll look like some sudden phase transition in our culture. This is obviously extremely speculative—both the data before 1950 and after our current era—but it sure does look like we might’ve transitioned into a new social paradigm as Kearney claims. In my last piece on 2024 predictions, I wondered what historians centuries from now will think about when they look at our time period. I made a few broad suggestions, but this change in single parenting is a sudden and abrupt shift that—as far as I know—has no precedent in our history. But the start of that phase transition does not line up with the 1980s.

Imagine that we do stabilize at our current level for a long time. Will historians a century from now look at this and say, “I guess the economy was just kind of bad in the 1980s?” Will they ignore that this rise started in the 1960s when the economy was better for working class men? And also ignore that the economy was far worse a few decades prior, during the Great Depression, and this problem didn’t happen then?

A Simpler Hypothesis

I think it's worth taking a step back, and saying why do so many kids live with one parent? Overwhelmingly, they live with their mother, and the father is either gone or only partially around. But why? In one study she cites by the Department of Health and Human Services, they attempted to get fathers more engaged with their kids. It didn’t work. They found fathers willing to participate, but one obstacle was “that mothers would serve as ‘gatekeepers,’ restricting a father’s access to his child.”

In terms of solutions, Kearney says,

It might mean revisiting fatherhood rights…there is a clear need to orient our social policy away from the long-standing, nearly exclusionary focus on single mothers and children, and instead work to strengthen families in a more holistic way.

I find it odd that Kearney considers fatherhood rights as a potential solution to this situation, but never considers it as a potential cause of the situation. In the United States, when divorce became common in the 1960s and 1970s, the mother was given majority custody of the child, and the father would get fairly minimal time with the kid. Maybe a weekend a month or less. This gradually changed over the course of several decades, and now in forty three states, the default is 50-50 custody, and that is only adjusted if there is evidence of extenuating circumstances. However, when the parents were never married, the legal situation is much more similar to how it was for divorced fathers in the 1960s.

As we discussed at the beginning, Kearney notes that the issue isn’t a rise in divorce, it’s a decline in the parents never getting married in the first place. She focuses on marriage not because she’s a conservative, but because she shows that married fathers spend more time with their kids than non-married fathers. But we could rewrite the entire premise of the book from “Why is there a decline in two-parent families?” to “Why is there a decline in parents who have the legal right to see their kids?”

Kearney references an ethnographic study, Promises I Can Keep, where they interviewed single mothers and found “many women don’t marry the father of their child because they do not see him as a reliable source of economic security or stability.” It seems that there’s the underlying legal cause, and then there’s the economic issue that decides who will be afflicted. Imagine a thought experiment where some foreign country reversed the legal situation, and fathers had the legal ability to “gate keep” low-income mothers. If (in this thought experiment) we found that there was a surge of children without mothers starting around the time that this legal situation started, and continued unabated through economic times both good and bad, I doubt we’d say, “It must be economic.”

One thing that I hoped to get was a better sense of the percentages of the underlying causes. On a personal note, I know people who don’t have a parent due to various reasons: the death of a parent, or abandonment, or due to gatekeeping from the mother. These are personal anecdotes though. And rather than personal anecdotes, I’m curious about the actual percentages of each cause. For example, the surge in single parents also correlates with the War on Drugs, when the number of men incarcerated rose by about five fold. Kearney mentions this as a contributing factor, but exactly what percent of single-parent families is caused by this incarceration rate? Exactly what percent is caused by abandonment? Exactly what percent is caused by gatekeeping? Without those hard numbers, it’s difficult to reason about this problem without resorting to culture war arguments and ideological beliefs.

I think the academic response that Kearney has received is unfortunate, because she’s made a convincing argument that these class divisions really could get calcified into our society for a long time. She’s also convinced me that economics is a contributing factor in which families are going to become single-parent families. But I don’t see evidence that economics is what started this situation.

See Kearney’s Figures 1.1, 2.1, 2.2, 2.4, 2.5, etc. Not until chapter 4 do we see what happened earlier.

Some thing else happened in the 1960's. The advent of the "pill". Prior to that, sex was a high risk event for women. Women (and society) viewed sex as something that the man had to pay a high price to get. (Commitment, marriage, stability). When the sexual revolution happened, the price that men had to pay to get sex went way down.

High cost for sex is an evolutionary strategy, and many species females require males to pay a high cost to get it. When the price men had to pay went down, so did marriage and single parenting went up.

As a primary caretaker of children and home, I know first hand that raising a family takes many hours of unremunerated labor that usually falls upon women. Currently I am not earning an income which makes me dependent and without access to economic power and opportunity. All these pro-life government people need to acknowledge and fix that. Har har.

Traditional gender roles create a class of unpaid labor (women) to support those with access to economic and professional power (men). Christian Nationalist movements are all about this. Brainwash a class of people that it is to their benefit and absolute privilerdge to not have any personal agency because they are able to raise the children of the person they are dependent on.