A few months ago, I wrote a review of Richard Reeves’ book, Of Boys and Men. There was a lot of good material in the book and I should have spent more time emphasizing the parts I agreed with. However, I did have concerns with the education statistics he presented and his interpretation. I reached out to him and suggested we do a forecasting competition to predict enrollment rates for men and women in college. While Reeves did not participate, I decided to do it anyway, and fortunately it led to some great discussion with a number of people who were also interested.

Much of the discourse around this topic has been framed within the narrative of the culture war, and the discussion has proceeded with exactly the decorum and grace you would expect from the culture war. I’d like to do my best to sidestep this debate and simply forecast the issue, specifically, the college enrollment gender ratio.

A lot of people have written on the topic, but I seem to be the first person to attempt to forecast this change. If you’re aware of any existing quantitative forecasts, please let me know. Forecasting the issue seems like an important thing to do if you want to understand the mechanism driving the change.

Over the past several decades, male enrollment has plummeted relative to female enrollment. Currently, there are roughly 70 men in college for every 100 women. To put this in perspective, after the Second World War, among people age 20 - 29, there were 72 surviving men in Soviet Russia for every 100 women. After the First World War, there were 67 surviving men in the United Kingdom for every 100 women.

This change is historic in terms of scale and magnitude, but the media is largely silent on the issue. The shift is so pronounced that it has led to gender ratios that are showing up in census data. Jon Birger looked into this in 2015 and found that “In Manhattan, the pool of 24-and-under college grads has 38 percent more women than men. In Raleigh, North Carolina, the gap is 49 percent. In Miami and Washington, D.C., it’s 86 percent and 49 percent, respectively.” This is a book from 2015, and these numbers have gotten more extreme since. A disparity of this size is causing cascading problems with 2nd order and 3rd order ripple effects across our society that are outside the scope of this project.

What is going on? What is driving this massive change?

1) My Model

I decided to focus on California specifically, because they release their data quickly and I’ll be able to get feedback quickly. The data for the entire US often comes at a two year lag, but California releases their data typically in February or March following the fall semester. So I’ll know in about seven months whether I’m accurate, rather than two years. California also has a population of about forty million people, comparable with a mid-sized European nation, so it’s a substantial sample size. If the outcomes from California were wildly different from the rest of the US, then this wouldn’t be helpful. Luckily, California appears to be a very good proxy for the rest of the United States.

You might think that this is due to changes in learning outcomes or academic achievement. But the gendered learning gaps in grade school have remained incredibly consistent for decades, while our college campuses simultaneously transitioned to a gender ratio you’d expect to see if we just fought a world war on home soil using Soviet-era tactics. This implies that the changes in enrollment rate is unrelated to learning outcomes. But if learning outcomes aren’t the problem, then what is happening?

First, let’s double check the learning outcomes. The SAT math gap has remained fairly consistent for half a century, narrowing slightly when the test was changed.

You might say, this could be due to survivor bias with only high-achieving students taking the SATs. But when we look at 8th grade math NAEP scores we see a very similar trend, with boys ahead by a tiny amount, but not changing.

And we see a static gap on 12th grade NAEP reading:

I think we can confidently say that the changing college enrollment gap is not due to changes in learning outcomes.

We see another persistent gap in GPA that is not getting significantly bigger or smaller:

A static input variable (GPA gap, SAT gap) is not driving a changing output variable (college enrollment). So then what is changing?

Before I answer that, let’s take a moment and think about how strange it is that the boys are ahead on standardized tests, but behind on GPA. It’s particularly strange when looking at the top decile. Boys make up about two thirds of the top decile for both math and reading, but only about one third of the top decile for GPA. Where are the missing boys?

A 2008 study in Israel found that when comparing blind versus non-blind scores (where the person scoring the test knew or did not know the student’s gender) “that male students face discrimination in each subject…However, the size of the difference is very sensitive to teachers' characteristics, suggesting that the bias against male students is the result of teachers', and not students', behavior.” This is not just an Israeli phenomenon. A Czech study also found that “teachers’ grading is biased in favor of girls both in mathematics and in native language.” They were able to rule out causes but were not able to provide evidence for what is causing it: “The gender effect in grading is sizeable across the whole performance distribution and can be explained neither by the students’ differing perceptions of stress at exams, nor by the students’ attitudes toward the subject in question.” They speculate the cause is behavioral, but don’t provide any evidence to support that. A Portugese study found there is a “a significant bias in favor of girls when they are assessed by their teachers” and that “Systematically over grading girls may be responsible for the increase in female enrollment rates at higher levels of education”. It does not identify the cause of the grading gap though. One Swedish study with 112,000 students finds that “girls are better rewarded than boys in teachers’ assessments” but another Swedish study with 1,700 students finds that this is not due to grading discrimination.

But what is the cause of the gap? Some say it is sexism and others say that students who cause more trouble are sometimes punished using grades. A long-term study in Norway followed 2,000 students for 10 years and found that when students are graded by someone who doesn’t know their gender, the boys scores go up and the girls scores stay the same. The researcher found that the boys whose grades go up tend to be troublemakers and that the teachers were using grades as a disciplinary tool. However, a British study found that there was also bias against boys in grading, but “This bias is not explained by girls' better behavior.”

An Italian study, which appears to be the largest sample size at 39,000 students says, “Results show that, when comparing students who have identical subject-specific competence, teachers are more likely to give higher grades to girls. Furthermore, they demonstrate for the first time that this grading premium favouring girls is systemic, as teacher and classroom characteristics play a negligible role in reducing it.”

Taking the various studies as a whole, they overwhelmingly find evidence that boys get lower grades for the same academic achievement, but the cause is unclear. Two studies indicate sexism from teachers. One says it is not due to sexism from teachers. Another study indicates this is due to teachers using grades to as a disciplinary tool, and boys are disciplined more often. And then a fifth study argues this is systemic, with individual teachers not having an impact. Clearly, more research is needed to pin down what is happening. I can’t find US studies investigating this. If you’re aware of any, I’d be curious to take a look.

If the cause is due to troublemaking behavior, then you could call this either grading discrimination in terms of their intellectual achievement or accurate grading in terms of the boys’ conscientiousness. My two main points are: 1) The GPA gap isn’t due to academic achievement and 2) it doesn’t seem to be changing significantly, just like with the NAEP/SAT scores. This means that whether it’s troublemaking or sexism, it does not appear to getting worse in the US. So we can once again rule this out as the direct cause of the changing enrollment gap. This is going to come up again later though.

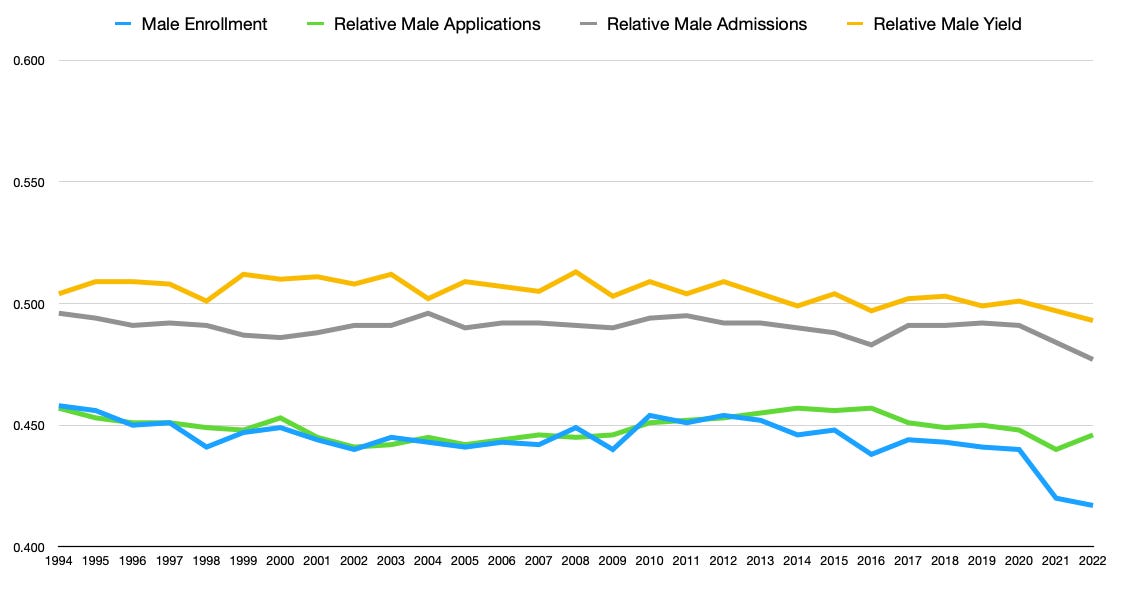

But back to what is changing. Let’s breakdown the pipeline into three stages: applying to college, getting admitted to college once students have applied, and the decision to attend given an admission (what colleges call “yield”). Let’s look at the application ratio first. I took the ratio of male to female applicants and excluded non-binary and trans students for simplicity. We see that for the first two decades of California data that the enrollment and application rates were virtually identical. For my purposes, forecasting enrollment was as simple as forecasting applications since they were so correlated. Then around 2012 they diverged.

The acceptance rate fluctuates wildly over time, but I looked at what I’m calling the relative acceptance rate with male acceptance rate divided by male + female acceptance rate. If men and women applied in equal numbers, when this relative rate is 0.5 then we’d have an equal number of acceptances. I did the same for yield.

Prior to 2012, forecasting enrollment was as simple as forecasting applications since they were virtually identical. But they began to diverge in 2012. Increasingly, schools have begun down weighting standardized test scores and instead shifting to GPA, where the boys are at a disadvantage. In 2021, the UC system stopped using SAT/ACT scores entirely. I’m not sure why California made this change in 2021, but I know that many universities talked about it as a response to the 2020 George Floyd protests because of concerns over racial gaps on standardized testing. So what do UC universities now use for admissions criteria? GPA, “personal qualities”, “Likely contributions to the intellectual and cultural vitality of our campus” and “Other achievements in any field of intellectual or creative endeavor, including the performing arts, athletics, community service, etc.” A study found that between 2005 - 2016 schools that down-weighted standardized tests for the admissions process accepted fewer men.

But how does UCLA quantitatively estimate an applicant’s likely contributions to the cultural vitality of the campus? How does UCLA quantitatively estimate their personal qualities? I’m not sure how these personal characteristics are assessed. Are they in person? Are they by essay? I need to figure this out in order to forecast the acceptance rate. I’m at a bit of a loss here. In order to accurately forecast their acceptance rate, I need to forecast how UCLA officials will assess applicants’ “personal qualities.” How do I do that? Relative acceptance rates for boys are at an all-time low for California. Out of a pool of an equal number of male and female applicants, only 47.7% of the acceptances will be male.

Until I get more information on this, I’m going to assume that the dip in acceptances for men in 2021 was due to this change and it will remain static for now. The application rate has been fairly stable for decades. The yield did drop a little the last few years, I assume due to the pandemic. It was pretty stable prior to that. I’m going to assume that now that the pandemic is over, the yield will return to pre-pandemic levels. However, the acceptance rate will stay at post-2021 levels because they’ve kept that criteria in place. The application rate will remain where it was before. This means that I expect a very slight increase for 2023 enrollment.

Forecasting sociological phenomena right after a global pandemic would be difficult on its own, but this was a global pandemic when we rolled out remote schooling in an untested way. The next few years are going to be particularly uncertain when it comes to educational outcomes. That said, with low confidence for fall of 2023, I’m going to predict 44.6% male applicants, 47.7% relative male acceptance rate, and 49.7% relative male yield rate, and an overall 41.9% enrollment rate. This is a very slight increase over fall 2022 at 41.7% male. I’ll check the data here in February.

2) Other Ideas

Christina Hoff Sommers was the first to talk about this at the national level in the 1990’s. Her book, The War on Boys, argued that boys and girls have different learning styles and schools had been reshaped to suit girls’ learning styles. But the learning gaps between boys and girls are incredibly static, so how would these static gaps translate into a changing output? Richard Reeves argues that boys develop later than girls putting them at a disadvantage in terms of brain development, arguing that this causes behavioral issues. I’m unclear how this would be translated into a predictive model that would explain the changing enrollment statistics. These authors both make valuable points about how we could improve our education system, but I’m very narrowly focused on whether these ideas have predictive value.

In her book, The End of Men, Hannah Rosin predicted that these gender ratios would naturally even out, arguing that “There’s nothing like being trounced year after year to make you reconsider your options.” Jon Birger made a similar forecast, arguing that the gender ratio would naturally even out as young men would be enticed by the idea of attending colleges filled with eligible bachelorettes. What these two forecasts both have in common is that they assume that things will just naturally even out without intervention. But 11 years later for Rosin and 8 years later for Birger, neither of these forecasts have come true. Clearly, neither of them fully understood the mechanism driving these changes.

Another popular argument is that boys are spending too much time playing video games. However, once again, we can see that video games are not having an impact on learning outcomes, because the gap in learning outcomes isn’t changing, even as boys spend significantly more time playing video games.

3) Long Term Forecast

This is often described as a recent phenomenon, and I suppose “recent” is a relative term. But this has been going on for basically everyone born in 1959 or later. That’s the last five years of the Baby Boomer Generation, all of Generation X, all of the Millennial Generation, and so far all of Gen Z. If any racial or gender group other than men was underrepresented for three generations, we wouldn’t just say that they’re an underrepresented population among college students. We would say that they’re historically underrepresented. That’s a contentious term in the culture war, because it confers prized victimhood status, but it’s simply a factually accurate way of describing the situation. Babies born today have on average more grandmothers with college degrees than grandfathers. That’s certainly going to have an impact on how children see who is supposed to go to college and who is not.

What was driving this change in the 1970’s is likely different than what is driving it in the 2020’s. In the 2020’s, this is often phrased as “men giving up on college” and yet, that doesn’t seem to be true. Based on application and yield data, men’s interest in going to college has remained relatively stable for the past three decades. The last 30 years of changes in enrollment look almost entirely explained by changes in admission criteria.

I think that this ratio is going to plateau for a long time. However, one other possibility is that we get into a negative feedback loop. The US is bifurcating into two groups: upper middle class kids with two parents who both have college degrees and working class kids with single parents without college degrees. Because children’s role models tend to be their parents and grandparents, boys are not as likely to have male role models with college degrees than girls are to have female role models with college degrees. Upper middle class boys will continue going to college at comparable rates to girls. Male relative enrollment will decrease until it hits a limit with boys with a college educated father continue going to college at high rates.

My three year forecast, for fall of 2026 is 41.8% male and five year, for fall of 2028 is 41.7% male.

Excellent article. Not that I am a follower, but I stumbled on a Dr. Jordan Peterson interview where he predicted, qualitatively, that after most men have left the university, in a few years women will notice and follow suit. Of course that is different from the gender ratio, but a decline in women students propping up these institutions would upset the balance. Not necessarily towards men though, as administrators start screeching "Bring back our girls!" and enact even more women-centric recruitment and retention programs. Thoughts?

I'd love to see this analysis spread more widely, and have one suggestion to that end. You've shown how the declines are not driven by changes in male learning outcomes. That's a very important part of the story, because it eliminates a lot of possible causes. But I predict that would be the most contested part of your analysis: partly for culture war reasons, but also because most people aren't accustomed to thinking of the PSAT and SAT as demonstrating learning, as such (as opposed to ability, or for some, test prep). I think it's worth making that case more forcefully, with additional (and perhaps different types) of data, if it's out there.