Response to the comments on Two-Parent Privilege

Answers to your questions.

There were a lot of good questions from my last book review of Two-Parent Privilege and I think it’s worth answering them for a larger audience.

Exceptions to the Rise of Single Parenting

Phillip Michaels asks why so many single families are concentrated in the South:

Love the commentary and data here. I do wonder why there isn't some discussion of the concentration of single parenting families in the rural South as shown on the US map graphic. Might the national data be driven by events that are actually focused mostly in the non-urban South?

Economic geographers describe five main geographic clusters of poverty in America:

Appalachia.

The second is referred to by economic geographers as the “Black Belt” in the southeast, where large numbers of slave plantations were concentrated. This band stretches from Louisiana and runs through the lowlands of the Mississippi, Alabama, on up through North Carolina. The former plantations of Virginia have largely been replaced by wealthy DC suburbs.

Counties along the Mexican border with large numbers of recent migrants.

American Indian reservations in the west. This “region” is non-contiguous with some scattered up in the Dakotas and some farther south in Arizona and New Mexico.

Urban poverty that doesn’t show up on a county-level map.

You can see the first four clusters here:

But when we switch from a map of poverty to a map of single parent families we only see three of those clusters: the border, reservations, and the Black Belt. Appalachia disappears.

To me, the interesting part is the Appalachian exception. It seems to be the only area of poverty in America where there is not also a high concentration of single parenting. Kearney doesn’t mention this at all—I’ve actually never seen anyone mention this—but I’m curious what’s going on in Appalachia.

But there aren’t just regional exceptions. Louise Kowitch mentions Asian American rates of marriage:

When education scores include data on ethnicity, the landscape changes. I would be very curious to know if that would be the case with marriage. For example, if you look at Asian Americans, marriage, educational attainment, income levels and crime are starkly different from that of other groups. Where does culture figure in?

This is a good point. About nine out of ten Asian American children live with married parents. Kearney’s argument focuses heavily on how college attainment for men leads to higher incomes, which leads to high marriage rates. But this narrative doesn’t apply to Asian Americans. Among Asian American children whose parents have less than a high school education, 88% of them live with parents who are married or cohabitating. That’s equal to or higher than white, Hispanic, or Black children of parents of any education level. As Louise asks, where does culture fit in? Kearney’s narrative is that women get picky about men’s income levels and also that men withdraw from marriage when they don’t make enough money. But neither one of those things is happening with Asian Americans. Clearly, culture is having a big impact.

Decline of Marriage for Everyone

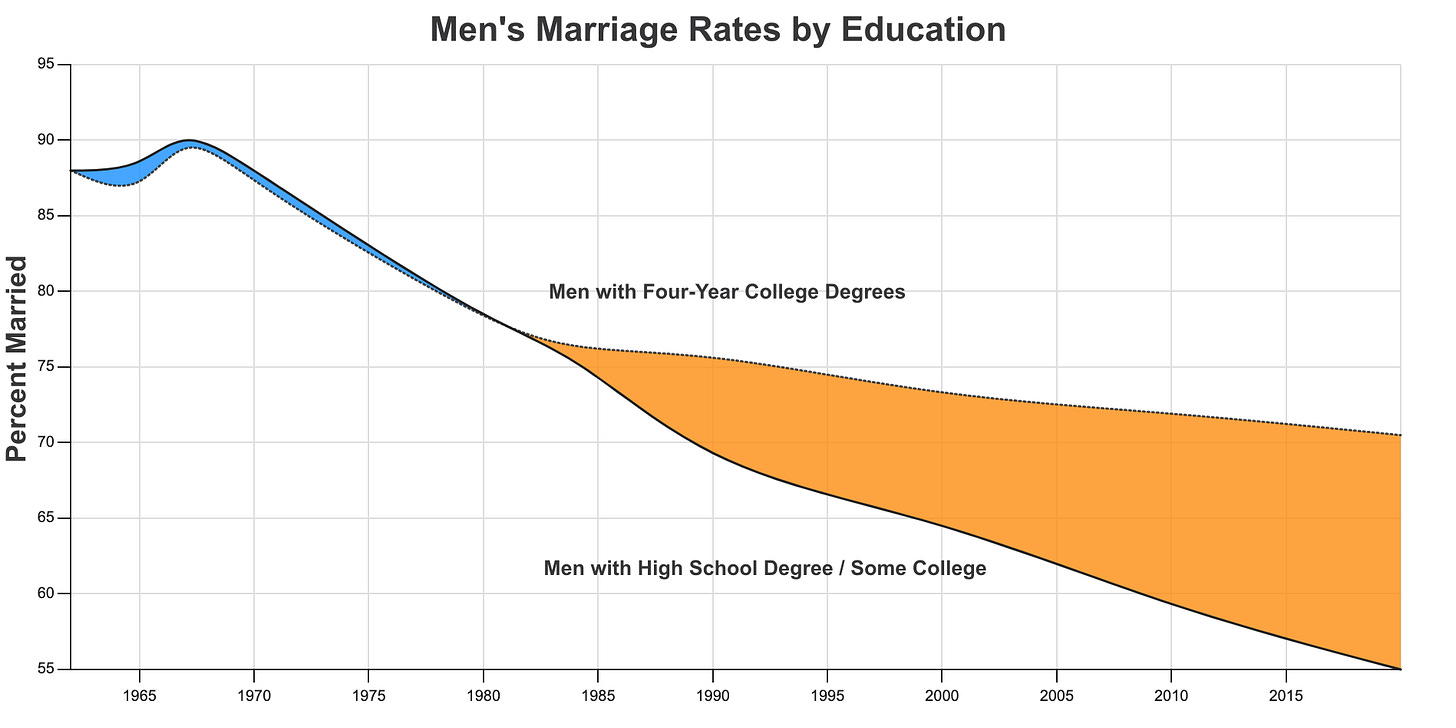

Arthur points out that the marriage rate for college-educated men is also falling:

I am not sure if I know how to read the graph but isn’t marriage rate for men with degrees declining as well?

Why you don’t mention it in the article?

Kearney’s main thesis is that single parenting could lead to entrenched class divisions because marriage has declined more quickly for men without college degrees. But she does bring up falling marriage rates for men with college degrees. Kearney initially argued that she wasn’t concerned about the children of wealthy parents who get divorced. As she dug deeper, she changed her mind:

…household income at birth is only partly responsible for the differences in outcomes. Even when we statistically adjust for household income (in addition to the demographic factors), sizable differences in outcomes remain. Put another way, a child born in a two-parent household with a family income of $50,000 has, on average, better outcomes than a child born in a single-parent household earning the same income.

Kearney notes that the children of wealthy single parents have (on average) worse outcomes as well, when compared with other wealthy children with two parents. But she focuses on these lower-income households because single parent families are growing much more quickly among lower-income households.

I want to emphasize that there are plenty of exceptions to the issues that Kearney raises. Barack Obama grew up with a single mother and his career went just fine. Clearly, a child of a single parent can grow up to be the most powerful person in the world, but Kearney focuses on averages.

Welfare

Several people brought up welfare. Andy G writes:

In an otherwise fabulous review, I’m quite surprised that you don’t note the Great Society welfare programs that made it economically much easier/possible for single women to raise children on their own, and actually provided economic incentives to have those children. Whether Kearney herself covered this in detail, in brief, or not at all.

This is clearly a material economic factor that is different than men’s incomes.

And it buttresses your argument re timing.

Kearney worked at a welfare-to-work program when she was in college and then spent much of her career as an economist focused on defending it. She argues that the rise of single mothers is not due to welfare. She points out that most of Western Europe has far strong stronger welfare systems but also have lower rates of single parents. She also argues that welfare benefits have declined in the US since 1980, while rates of single parenting have increased. Kearney doesn’t argue that there’s no connection, but that it’s a small one:

…it is well documented across dozens, if not hundreds, of academic studies that any link between welfare generosity and the incidence of single-mother households in the US is, at most, small…a large body of studies on the topic produces estimates that are consistent with a small real effect on marriage and family formation outcomes, but one that is sensitive to methodology. If there were a sizable effect, it would be more readily and consistently replicable across studies and statistical approaches.

She doesn’t say that there’s no impact, but that it’s “small” or not “sizable.”

The main counter argument to this is that these studies are limited in the observed range. One example of issues that pop up when you have a limited range of observations is Berkson’s paradox. An example of that is the common mistakenly held belief that standardized tests do not predict GPA. The SATs can have scores up to 1600, but an individual college might have most of its acceptances within a narrow range of 200 to 300, so looking at within that range there appears to be little correlation between the standardized test and the college grades. But if you look at people say scoring so low that they never even should go to college on the first place, then suddenly the SATs look very predictive. What happens when you look outside the observable range?

I don’t think that welfare is a perfect example of Berkson’s Paradox, but something similar. Christoper Jencks, a Harvard social scientist, wrote in Making Ends Meet (although I found this via Bryan Caplan):

Although liberals scoff publicly at these arguments, few really doubt that changing the economic consequences of single motherhood can affect its frequency. Imagine a society in which unmarried women knew that if they had a baby out of wedlock their family would turn them out, the father would never contribute to the baby’s support, the government would give them no help, and no employer would hire them. Hardly anyone, liberal or conservative, doubts that unwed motherhood would be rarer in such a society than it is in the United States today.

You could also think about the reverse. In a society where women were paid millions of dollars to be single mothers, hardly anyone would doubt that these economic consequences would affect its frequency.

Jencks full argument here is that the academic studies are limited because they only look at a narrow observed range. Based on that reading, you might see Jencks as a tyrant, but he’s actually quite sympathetic towards single mothers. Jencks has an interesting article on it in “The Hidden Paradox of Welfare Reform.” He looks at the international data on whether single mothers correlate with men’s incomes. Rather than use education as a proxy for income, he just directly compares the difference in household income between single mothers and married parents across Europe:

If women's decisions about their living arrangements were shaped mainly by economic considerations, single motherhood should be relatively common in Spain and Italy, somewhat less common in the rest of Europe, and least common in the English-speaking world. Yet the graph shows precisely the opposite pattern.1

Jencks concludes that the rise of single mothers is primarily driven by social and cultural forces, not economic.

The main contradiction I see is that Kearney models women as rational economic agents when it comes to choosing which men they want to marry, but suddenly not economically rational agents when it comes to welfare. When it supports her argument, women are economically rational. When it’s inconvenient, suddenly women are not economically rational.

In Kearney’s defense, those studies are all within the observable range, and as she points out, they don’t find that it makes much of a difference. I agree with her that it’s probably not the economic consequences of welfare that have caused the surge of single parenting. But if it’s not welfare, then what did cause it?

The Pill?

Quite a few people brought up the birth control pill. Carol Shetler writes:

I'm going to toss out an idea that supports the decline starting in the 1960s. That was when the birth control pill became widely available around the world. Women realized fast that they did not have to have kids every year and then need a husband around for both economic and emotional support of those (often unwanted in the past) children. They could postpone having kids, so that meant they could postpone getting married too. Eventually the position became that "Hey, I'll have my kids when I want them, husband or no husband. And if the dad wants to be involved, bonus, but if not, well, no problem. I'm not getting married to someone I can't live with just to have a baby daddy around." I think this could be a major factor.

I was a bit confused by this at first. I’m not a doctor, but my understanding is that taking a birth control pill makes women less likely to become a mother of any sort—a single mother or otherwise. But I don’t think these arguments are really saying that it’s the pill, but rather the changes that came after the pill. It’s tough to have a career when you have eight kids by the age of thirty like women did in the 1800’s. I’m sure there could be a debate about whether the pill or feminist activists enabled the surge of women’s labor force participation, but I think Carol is talking about having a career when she mentions having a husband around for economic support, and not the actual estrogen tablets.

I think that everyone would agree that the rise of single parenting would have been impossible to happen without the changes of the 1960s: divorce and the pill and women’s large scale entry into the workforce. I think that everyone would agree that those changes are necessary, but not sufficient, for this to happen. College-educated women have access to birth control and also the most economic independence, but those are the women who seem to end up with husbands. Asian American women have access to the pill and their marriage rates aren’t much different from the average American family before the pill. Also, the US has far higher rates of single parenting than Europe, but women in Europe also have access to the pill.

This takes me back to my conclusion from the book review. We know there are a lot of factors. We know that some parents are just absent, but Kearney doesn’t say what percent. The ethnographic studies show that gatekeeping is a major factor, but those aren’t surveys and so we don’t know exactly what percent of single families are caused by gatekeeping. We know that there’s been a five fold increase in incarceration rates since 1960—particularly among working class men—but I’m not clear what percent of single parent families are caused by this. We know that there’s been a massive surge in addiction since 1960, but again, I’m not clear what percent of single families are caused by this. I’ve seen a lot of people with a lot of very strong opinions on this topic, and I’ve reached out to several of them to ask for this information. So far, no one seems to actually know. Until I can find even a vague estimate on those things, I think that everyone is just speculating.

If I can get some better data on this, I’d be interested in actually modeling it and forecasting it. But in the meantime, I’m going to be quiet for a few weeks while I work on a larger project that I’ll eventually post here.

This is an older study from 2001, and I’m curious how it’s changed since.

Wow! Wonderfully cogent analysis of the question. Thank you!

Great article. Shame we have no data for religious affiliations, often an important aspect of culture.