Jonathan Haidt’s new book, The Anxious Generation, is on track to becoming the best selling social science book of 2024. But it’s not just selling well. It’s also on track to become one of the most politically influential books on the impact of technology on society.

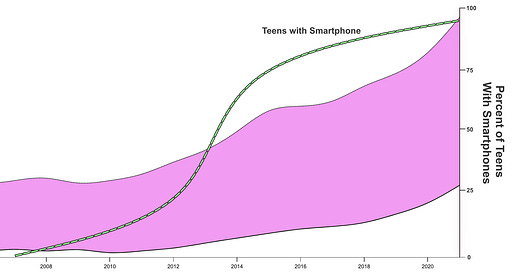

Haidt argues that the new digital childhood centered around smartphones has led to an epidemic of mental health disorders for children and teens. The book has set off a domino effect. Shortly after it was published the US Surgeon General called for warnings on social media like we do with cigarette cartons. Then immediately afterwards the LA public school district—which provides education for a population the size of Norway—took part of Haidt’s advice and voted to ban smartphones and social media in schools. Then Governor Newsom said he’s considering similar steps for the entire state of California. New York quickly followed suit. In the UK, two mothers self organized a group for a phone-free childhood and now they have tens of thousands of parents involved. They feature Haidt on their main page.

The book comes at a time of growing legal scrutiny of Big Tech. There was the 2021 Facebook Leak of internal documents that showed they were aware of harmful effects on teenage users. Canadian parents filed a class action lawsuit against the video game company, Fortnite, for addicting their sons. The parents of Uvalde shooting victims are now suing both Meta/Facebook and Activision (one of the largest video game companies in the world) for encouraging violence and radicalization. Haidt compares Silicon Valley to Big Tobacco and Big Oil for hiding evidence of the harmful impacts of social media:

A few of these companies are behaving like the tobacco and vaping industries, which designed their products to be highly addictive and then skirted laws limiting marketing to minors. We can also compare them to the oil companies that fought against the banning of leaded gasoline.

But Haidt wants more than to just take away smartphones in schools. He argues the entire mass migration from the real world to the digital world has been a mistake. His overall claim is that we’ve become overly protective of children in real life, rarely letting them leave the home without supervision and even arresting parents who make their kids go for a walk alone because of a societal fear that they’ll all be kidnapped or poached by sex predators. Meanwhile, half the internet looks like a rape dungeon and we drop off our kids at the front door and say, “Have a good time!”

There’s a lot at stake with Haidt’s argument. He claims there’s a mental health epidemic triggered by the collective technologies of smart phones, social media, video games, and pornography. He claims these technologies will lead to political radicalization. Haidt claims social media has dramatically reshaped culture by enforcing conformity. There’s also the potential that the technological advancements of the past couple decades will be viewed in the same way we see cigarettes and leaded gasoline. The Anxious Generation covers a lot of ground. These are all worth discussing, but out of all the ideas in the book, I want to focus just on a close reading of Haidt’s statistical argument that there’s a connection between digital technology and a mental health epidemic among children and teens.

When I dug into the statistics I found something strange. Since this is being framed in criminal terms, I’ll go with a crime analogy. Let’s say the police are investigating a double murder. Let’s call the victims Alice and Bob, who were killed at the same time and at the same place. The police identify a suspect, and the more evidence they collect, the more confident they are that the suspect definitely killed Alice. But also, the more they study the evidence, the more confident they become that the suspect didn’t kill Bob. But Alice and Bob were killed at the same time and at the same place. So who killed Bob?

Right around 2010, rate of anxiety, depression, and suicide all began to rise for children and teens. Boys and girls have different starting rates for these various problems, but they all started to rise at the time and about the same relative amount for each. After looking into it pretty thoroughly, I think we can confidently say that social media in particular not only correlates with mental health problems for teen girls, but really does cause these problems. However, boys have also had a surge in mental health issues at the same time and in the same countries, but the evidence points to a different cause.

At the core of the book is a prediction. Haidt has four specific policy proposals that I’ll summarize as digital minimalism: No smartphones until age 14, no social media until 16, no phones in school ever, as well as more unsupervised play in the real world. He predicts, “If most of the parents and schools in a community were to enact all four, I believe they would see substantial improvements in adolescent mental health within two years.”

Most of the public seems pretty onboard with Haidt’s argument. The phrase “Extremely Online” has become a synonym for crazy. Everyone can see teens (both boys and girls) stumbling around zombielike on their phones. But even though the public seems to broadly agree with Haidt, much of academia does not. It’s not always easy to establish a clear statistical causation between a cause and a disease. One of the most influential statisticians of all time, Ronald Fisher, was a lifelong smoker who argued that the connection between smoking cigarettes and lung cancer was just correlation, but not causation. He said that there might be some inflammatory disease that caused cancer and that cigarettes were just a tonic that soothed the inflammation. It took decades to figure out whether the connection between cigarettes and lung cancer was causation or just correlation.

Haidt has a lot of critics who argue that there’s a correlation between digital technology and mental health, but not causation. Haidt has a lot of critics in general. There are people who say there has been no surge in mental health problems. People who say that there has been a surge, but there’s no correlation. And there are people who say there’s correlation, but no causation.

I didn’t see Haidt give specific numbers for his prediction, which is pretty common for a lot of public intellectuals. So let’s look at his statistical argument to try to at least get a general sense of how we’d expect adolescent mental health to change if we put his policies into place, and also, what we think would happen if we don’t. To answer these questions, let’s look at the book through the lens of his critics.

1. Is anything actually wrong?

On October 1, 2015 the United States made a change to the way that diagnoses are classified with ICD-10 (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision), which impacted the way that mental health issues are reported. Some critics argue that this surge in mental health issues is really just an accounting trick, and not a real change in the underlying well-being of the population. But if this argument is true, then we would expect to see a sort of step function to occur.

Instead, we see a gradual rise in depression beginning around 2010 and continuing to rise years after these changes were put into place.

Additionally, this change wasn’t an American phenomenon. It occurred in every country with high-speed internet all around 2010, including countries that used ICD-11 instead of ICD-10.

But other people argue that yes, there really is an increase in the diagnosis of depression and anxiety, but that’s just an artifact of “diagnostic inflation.” They argue there hasn't been a worsening of the well-being of the population, but rather we’ve just expanded the definition of what it is to be anxious or depressed. Perhaps we’ve pathologized normal feelings and labeled them as Generalized Anxiety Disorder or Major Depressive Disorder. But the problem with this argument is that it’s not just that adolescents are being diagnosed with mental health disorders more often by clinicians, they’re also committing suicide more often and the increase in suicide was synchronized with the increase in diagnoses of other mental health problems.

Once again, this isn’t an American phenomenon, but is happening internationally in Canada, the UK, Australia, New Zealand, Sweden, etc. I’m on Haidt’s side on this one. There really is a surge in mental health issues. But a lot of things have happened in the world in the past couple decades. So what is causing it?

2. The Potato Critics

Since social media is still so new, the first major study wasn’t done until very recently, in 2019. The study had a massive sample size of 350,000 and asked teens about their “digital media use” and their mental health. Their conclusion: digital media use explained “at most 0.4% of the variation in well-being.” The media pointed out that the correlation between digital media and mental health was so tiny that it was comparable to the correlation of eating potatoes and mental health. The paper was titled, “The association between adolescent well-being and digital technology use” but I’m going to call it the Potato Study for short.

The Potato Study defined “digital media use” as anything from watching Netflix to reading a novel on your computer. Haidt and his collaborator, Jean Twenge, got access to the same dataset and re-did it but zoomed in on social media use and teen girls. They found a correlation of about 0.2. This correlation seems to replicate across many studies, and aggregating those studies together finds a correlation of about 0.2 between social media use and girls’ mental health. For boys, it seems to be about 0.06.

The conversation here started with the Potato Study and then Haidt and Twenge’s rebuttal was that there was a correlation of 0.2 for teens girls. But in psychology, a correlation of 0.2 is considered so small that it’s labeled as negligible. The Potato Study was done by researchers at Oxford, one of the most prestigious universities in the world, and published by Nature, one of the most prestigious journals in the world. It carried a lot of weight with both academics and the media. Many people in the field see 0.2 as almost laughably small. So when Haidt and Twenge showed that the correlation was 0.2 their argument wasn’t well received.

3. Critics who argue there is a correlation, but 0.2 is a negligible correlation

There are a couple very different ways of interpreting that correlation of 0.2. There are two main schools of statistics: frequentism and Bayesianism. Academic social science is dominated by frequentists. Frequentists care very much about defining boundaries and then calling anything above/below that boundary strong/medium/weak correlation (or significant versus non-significant for other methods). Some people say that anything below 0.4 is a weak correlation. Other people say anything below 0.3 is a weak correlation. But pretty much all frequentists see 0.2 as a weak correlation.

In contrast, Bayesians say that a single correlation in isolation isn’t terribly informative. They say what matters is the relative strength of the correlation to the competing explanations/hypotheses. For example, say that someone proposed that this was all due to exposure to microplastics and someone else said this was due to exposure to stress from hostile political rhetoric. If the correlations for those two hypotheses were both much lower than 0.2 then that provides us important information about which hypothesis is more likely to be correct.

Likewise, if it turned out that exposure to microplastics had a correlation of 0.8, then that completely changes how we interpret social media’s correlation of 0.2. But academic social science is dominated by frequentists, who very much care about those boundaries. This is part of why Haidt has had to fight an uphill battle to get his argument across: many frequentists are going to dismiss 0.2 as inconsequential.

Haidt doesn’t take the Bayesian approach, but instead references an argument by Chris Said that “Small correlations can drive large increases in teen depression.” Imagine that you have some disease that affects 1 in 100 people. Then you have some pill that has a side effect where 1 in 100 who take the pill also get that disease. And then everyone in world all starts taking that pill. Suddenly 2 in 100 people have the disease. It’s just doubled overnight.

Haidt argues that this is what has happened since 2010 with social media. My point is that sure, it’s possible that this 0.2 could lead to a massive spike in mental health problems, but also, it doesn’t really convince me that much without knowing enough about the alternative arguments. Haidt has a much more convincing argument though.

4. Critics who argue that there’s correlation, but no causation

Haidt references what he calls “quasi-experiments” where high-speed internet was rolled out to different regions of Spain at different times. You can think of the different regions as control groups and test groups. And in the test groups where they got high-speed internet, there was an almost immediate spike in teen girls going to the hospital for incidents of self harm. They found: “Girls drive this effect entirely.” The title was “High Speed Internet and the Widening Gender Gap in Adolescent Mental Health: Evidence from Hospital Records” but I’ll call it the Spanish Fiber Optic Study for short.

Among teen girls, there was a 112% increase in self-harm and suicide attempts. A 112% spike in hospitalizations from self-harm and suicide is enormous. Haidt found five different studies from different countries that used this sort of methodology. All five replicated the same results. At this point, I’m very much on Haidt’s side. I think we can confidently say that for teen girls, yes, social media causes these issues and doesn’t just correlate with them.

For good measure, there’s also the dose-response studies:

5. What’s driving boys’ mental health problems?

When you look at the big picture, the mental health impacts don’t seem terribly different between boys and girls. Haidt summarizes the situation:

Beginning in the late 2000s and early 2010s, American boys’ rates of depression, anxiety, self-harm, and suicide began rising. Boys across the Western world began showing concerning declines in their mental health. By 2015, a staggering number of them said that they had no close friends, that they were lonely, and that there was no meaning or direction to their lives.

Rates of depression started higher for girls in the US in 2010 and rose by 145%. The starting rate of depression for boys was lower, but rose by 161%. For suicide, boys started out with a higher rate, and then increased by 91%. For girls, their rate of suicide started lower but increased by 167%. I’m not saying those numbers are exactly the same, but when you look internationally there seems to be a consistent pattern: they start at the same time and increase with roughly similar rates. At first glance, it would seem reasonable that they’re driven by the same cause.

Let’s remember the question we’re trying to answer here. Haidt’s core argument is that he proposes four policies and that “If most of the parents and schools in a community were to enact all four, I believe they would see substantial improvements in adolescent mental health within two years.” He’s vague on the specific impact. Without being more specific, then this prediction becomes somewhat non-falsifiable. Describing the world with precise mathematical detail is what separates science from pseudo-religious prophecy. So let’s look at his work to understand what will happen if we do, or do not, enact these policies.

6. Never mind, let’s talk about something else

Haidt writes:

…the hit to their [boys] well-being is seen less in their rates of mental illness (which did increase) and more in their declining success and increasing disengagement from the real world.

He says the problem is less with boys’ mental illness and more with their declining success causing them to fail to transition to adulthood and become NEET (Not in Education, Employment, or Training). If they’re having trouble transitioning to adulthood in their twenties, well that’s a problem we should be talking about. But that’s not the problem we’ve been talking about the whole book. He spent the first six chapters of the book showing one study after another that does show there’s a major increase in mental illness for boys. He particularly emphasizes the 10 - 14 age range. The thesis of the book wasn’t, “If you enact these policies then we’ll see a substantial improvement in the labor force participation rate.”

He spent the first six chapters of the book talking about how both boys’ and girls’ mental health has declined. But then, when he dives into what’s happening with boys (in a chapter literally titled, “What Is Happening to Boys?”) he largely stops talking about stops talking about boys.

Suddenly there’s a pivot to what’s happening to young men. He emphasizes that if boys get real world social skills and do better in school then they’ll be more prepared for the transition to adulthood and be less likely to become NEET. That sounds reasonable and is surely an important thing to talk about. But what is happening that’s driving up depression and suicide among boys in the 10 - 14 age range?

But, since he brought it up, what are the skills Haidt sees as critical for the transition to adulthood? Haidt emphasizes young men to do better in school, get a job, and most especially need to get better at:

…approaching a girl or woman in real life and asking her out on a date. These are the sorts of healthy risks that young men should be taking to become more competent and successful romantically.

I want to emphasize the young men part of that quote. I don’t think he’s arguing that the suicide rates of 10-year-old boys will drop if they just get laid more. The problem we’re talking about here isn’t the mental health of young men in their twenties who have transitioned to adulthood. The book is titled, The Anxious Generation, not The Incel Generation. The subtitle of the book is How the Great Rewiring of Childhood is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness and we’re trying to evaluate the core thesis of the book: What will happen to adolescent depression, anxiety, and suicide if his policies are put into place, and what will happen if they aren’t?

So then what drove the 91% increase in suicide among boys age 10 - 14?

7. What about video games?

Early in the book, Haidt says that the problems with boys “…usually involve video games (and sometimes pornography) rather than social media…” But later in the book he summarizes the research around video games:

When I began writing this book, I had suspected that video games would play the same role in explaining boys’ problems as social media does for girls…But after wading into one of the largest and most contentious areas of media research, I do not find clear evidence that would support a blanket warning to parents to keep their boys entirely away from video games. The situation is different from the many studies that link girls, social media, anxiety, and depression.

He does emphasize that some boys end up playing 6+ hours a day of video games, and that’s clearly going to have an opportunity cost: if you’re playing games that much then you aren’t going to have time to play sports or do homework. But playing video games for a few hours each week actually has some positive cognitive benefits.

Haidt does say that:

Video games offer boys and girls a number of benefits, but there are also harms, especially for the subset of boys (in the ballpark of 7%) who end up as problematic or addicted users. For them, video games do seem to cause declining mental and physical health, family strife, and difficulties in other areas of life.

But was gaming addiction among boys at higher or lower than 7% prior to the 2010 surge in mental health problems? Does it cause so much anxiety that it leads to the diagnosis of chronic anxiety that he argues will decline if we enact his policies? Without either of these pieces of information it makes it difficult to estimate how much this is contributing to the problem.

Haidt also looked into the research on pornography and found that there’s a lot of evidence that men who consume a lot of pornography become less attracted to their romantic partners. He finds that “Compulsive pornography users, who are predominantly men, are more likely to avoid sexual interactions with a partner and tend to experience lower sexual satisfaction.” But is this the problem that 10-year-old boys are facing?

He speculates that showing pornography to boys could cause problems in their future relationships. This seems like a reasonable speculation. But whether it impacts their future partners as adults or not is a separate question from Haidt’s thesis that digital minimalism would help the mental health of adolescents before they have those romantic partners.

Is there any link between pornography and anxiety or depression? Haidt looks at a meta-analysis of 50 different studies and finds less “interpersonal satisfaction.” I can’t find any mention in the book of a link between pornography and anxiety or depression in adolescents.

After looking at the mental health impact of social media and video games and pornography, Haidt concludes:

“I can’t point to one single technology as the primary cause of their distress.”

This is a strange thing to say on page 175 after the previous 174 pages talked about how the “great rewiring of childhood is leading to an epidemic of mental illness.” But maybe the problem isn’t a single technology, but rather the aggregate of multiple technologies that are causing the problem. So rather than look at studies that focus on a single technology, instead we need to look at studies that focus on the impact of the aggregate of multiple technologies.

8. Back to the Potato Study

Haidt does present studies that look at all digital media as a whole: Remember that the Potato Study looked at digital media use as a whole and found it only explained a 0.4% variation in mental health. Haidt re-did the study with the same data, but excluded boys from the study and zoomed in on girls, because that’s where he found statistically significant results.

The Potato Study isn’t the only study that looks at the aggregate impact of digital technology. There’s also the Spanish Fiber Optic Study that looked at the impact of high-speed internet.

You might argue that maybe boys are more impacted by social media than the studies are showing. The Potato Study was based on survey questions, so maybe you say that boys are just answering the survey questions differently. Maybe they’re less likely to say that they’re depressed when they really are. But the Spanish Fiber Optic Study isn’t based on survey data. It’s based on hospital records.

Importantly, the Fiber Optic Study showed that the rates of self-harm for boys only slightly changed relative to locations without high-speed internet. High-speed internet doesn’t bring one single technology, it brings social media and gaming and pornography. Haidt explains that the Fiber Optic Study replicated many times in different regions. I didn’t look through them all, only the one he highlighted as his centerpiece. He says that he “can’t point to one single technology as the primary cause of their distress” and the studies he highlights indicate that it’s not the aggregate of multiple technologies either.

I’m not the only one who finds Haidt’s argument somewhat lacking in evidence. Haidt summarizes his own argument: “My story is more speculative than the one I told about girls in the previous chapter because we just don’t know as much about what’s happening to boys.”

9. The Network Hypothesis

The most surprising thing about the book was that the evidence isn’t stronger. I have friends who have become socially isolated because they’re on social media or gaming all the time. They live their life on screens and have forgotten about the real world. What explains this gap between what I’m seeing and the statistical data?

In 2000, the political scientist Robert Putnam published his book, Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community, which covered all the ways that Americans had disengaged with their local communities starting around 1950. The core argument was that television had made it too appealing to just stay inside rather than engage with everyone around you. The Anxious Generation seems like a sequel to Putnam’s Bowling Alone.

Haidt emphasizes that the problem might not be directly caused by the use of technology, but rather collapse of our real-life social networks because everyone is on their phone all the time. If this network hypothesis is right, then we wouldn’t expect to find a problem by using a traditional dose-response model to see if social media / video gaming is causing a problem. After all, there’s no foreign chemical crossing the blood-brain barrier, so maybe all these statistics are flawed. Maybe the explanation for all the contradictions we see is that we shouldn’t be looking at the direct impact of technology on one person’s individual health, but rather the community, measured by how many hours people are spending in real life with each other.

When it comes to the girls, all the evidence lines up neatly. I think we can confidently say that the combination of smartphones and social media really do cause anxiety and depression in teen girls. But it’s not so clear when it comes to boys. Haidt acknowledges this once or twice, but then just plunges ahead regardless, confidently predicting that if we enact his policies we’ll see a substantial improvement in a couple of years. But I think Haidt’s right. It’s time for a reboot. I say enact the policies for a couple years, turn off the phones, and let’s see what happens.

This was a great writeup, and I thank you for it.